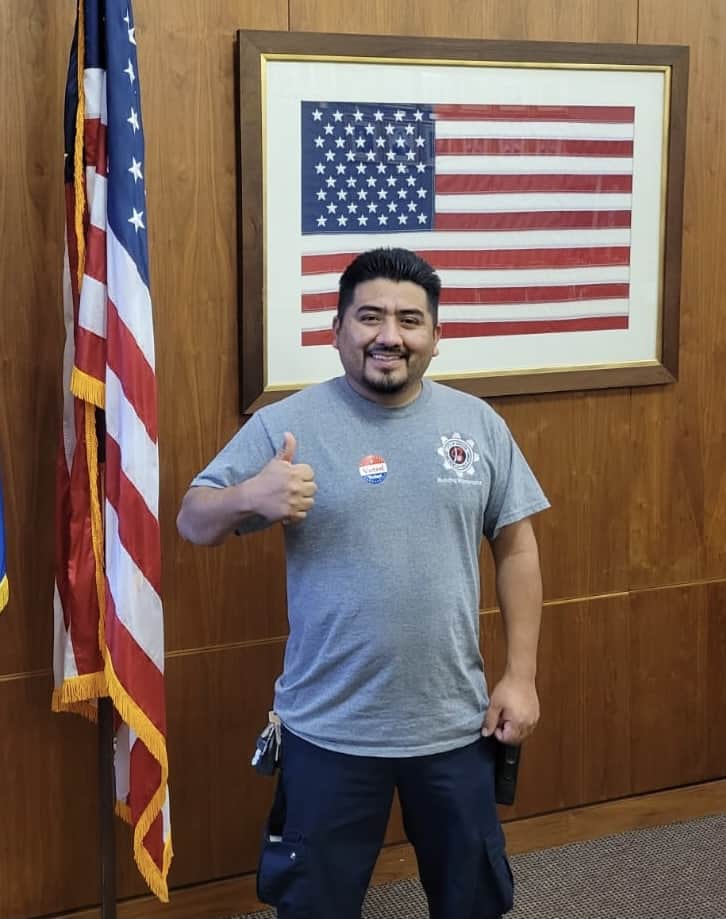

“If you don’t have the right to vote; you don’t have a voice – you’re in the shadows,” said Luis Lorenzo, a resident of Bristol, about the importance of exercising a citizen’s responsibility to vote.

Lorenzo is like the approximately 15 percent of Connecticut residents born in another country, according to the American Immigration Council. Many in the state’s Hispanic-Latino community come from the Dominican Republic (5 percent) and Ecuador (5 percent).

Those foreign-born residents cannot vote until becoming citizens, unlike the most significant number of Hispanic-Latinos in Connecticut: Puerto Ricans. As an incorporated territory, residents who move from the island can vote once they establish residency in the continental United States.

Lorenzo, who recently became a U.S. citizen, is originally from Mexico. “Now, with me becoming a citizen, it gave me the opportunity to contribute, to have a voice – not only for me but other people.”

He was one of the growing Hispanic-Latino voters participating in this year’s local elections and at the center of a changing electorate.

While the group reached a milestone in the 2020 presidential election with a record 32 million eligible voters, the largest minority voting group, and the country’s second-largest voter bloc by ethnicity, the number of naturalized citizens voting – plateau.

In 2020, voting by Hispanics-Latinos born in the United States was approximately the same rate as those who are naturalized U.S. citizens, according to a City University of New York study.

New Americans have historically trailed native-born Americans at the polls. In 2016, 54 percent of naturalized citizens voted in the general election compared with 62 percent of native-born citizens, according to Demos, a liberal think tank.

Much of the parity has to do with the increasing number of U.S. birth rates driving the more than 60 million population growth in the country versus immigration.

Still, experts say the low number of naturalized citizens participating in the electoral process is not for lack of interest, but rather barriers like language, inadequate representation in government, and outreach by both Democrats and Republicans.

“People feel excluded in not having the knowledge because of the language barrier,” said Lorenzo.

Reporter Maricela Baez, and Photographer/Editor Joe Rodriguez report for CTLatinoNews.com

In December, the Census Bureau issued its national list of states, counties, and communities where populations of eligible voters not proficient in English are large enough to trigger protection under the federal Voting Rights Act that requires language help for such voters.

Due to the high numbers of Hispanics-Latinos in communities like Bridgeport, New Haven, and East Hartford who are eligible to vote but are not proficient in English, Connecticut is on the list that rose from 331 this year up from 263 in 2016.

“For some Latino voters, it’s not that they don’t necessarily understand English; it’s that they don’t identify with the candidates,” said Valeriano Ramos, Director of Strategic Alliances, Everyday Democracy.

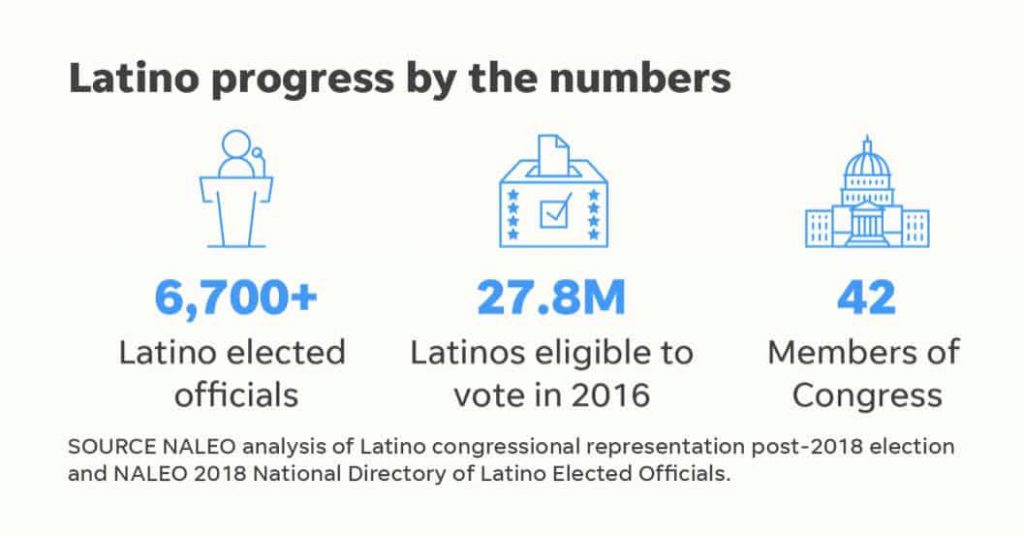

While Hispanics-Latinos make up nearly 20 percent of the country’s population – about 67-hundred elected officials are Hispanic-Latino, according to a 2018 analysis by the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials, or NALEO. That amounts to a political representation rate of just over 1-percent in local, state, and federal elected offices.

No Hispanic-Latino has ever held one of Connecticut’s six constitutional statewide offices. The same goes for the five Congressional seats. And except for 2001 to 2015 in Hartford, Hispanics-Latinos have not been visible in mayor’s offices. This November, Hispanic-Latino Democrats ran unsuccessfully for mayor in New Britain and Danbury.

SUGGESTION: Why Latinos Don’t Vote

The reasons why many Hispanics-Latinos do not vote in Connecticut are sundry and diverse. Often there are multiple factors – poorer urban residents may not have transportation and may be unfamiliar with local politics.

Thought leaders in the state explore poverty, mobility, exclusion, cultural and historical issues that can diminish voter turnout.

Another problem is the lack of attention both political parties pay to the Hispanic-Latino electorate, favoring instead to focus on traditional voters. For example, Werner Oyanadel, the Latino Policy Director with Latino policy division for the Connecticut General Assembly’s Commission on Women, Children, Seniors, Equity & Opportunity (CWCSEO said in an interview on the Latino News Network podcast, “3 Questions With…” that while it is a particular issue at the national level, “Connecticut is a safe blue state…and that’s why the Republican and the Democratic party do not reach out to the Latino community as much as they should.”

Culture Concepts, a private research consultancy, collaborated on a study that found eligible Hispanic-Latino voters feel disenfranchised due to sporadic outreach by campaigns. New voters or those who haven’t cast a ballot in recent elections are not actively courted through phone calls or door-knocking.

Lorenzo shared he was excited to be able to finally vote but warned, “Right now, I think there is a disconnect between the community and the candidates.”

The Pew Research Center found that 23.2 million naturalized citizens were eligible to vote in the 2020 presidential election, making up a record 10 percent of the total electorate. As we approach the 2022 midterm elections, an often litmus test for liberals and conservatives, the rift with new Americans, one of the largest voting groups in the United States, cannot be ignored.

Cover Photo Credit: Element5 Digital on Unsplash

Publisher’s Note: Voting System Fails Immigrants is the subject of the Advancing Democracy: Connecticut Solutions Journalism Initiative that CTLatinoNews.com (CTLN) is undertaking as part of eight reporting projects in 10 newsrooms across the United States.

Voting System Fails Immigrants presents some of the challenges with the Hispanic-Latino immigrant community of Connecticut participating in the electoral process. Beginning in January, CTLN will explore solutions to these problems by engaging with thought leaders in the state and drawing from the best practices and lessons learned in communities across the country.

Advancing Democracy: Connecticut Solutions Journalism Initiative is a six-month program sponsored by the Solutions Journalism Network (SJN); its mission is to spread the practice of solutions journalism: rigorous reporting on responses to social problems.