On a Tuesday afternoon in a Hartford courtroom, a small crowd of about 20 people waited to be called before the judge.

Some fidgeted nervously. None of them had a lawyer of their own.

U.S. Immigration Judge Ted Doolittle called them forward, one by one, to the table facing him. An interpreter sat to his right, and an attorney from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was on a video monitor.

Those waiting their turn listened closely to the interpreter.

“I am looking for a lawyer, but most either don’t answer or say that they are busy,” one woman told Doolittle. “I’ve looked for them, contacted a few, some didn’t answer and some didn’t want to take my case because they were working on other cases.”

The lack of an affordable and available lawyer was the common thread that bound this group together.

Immigration courts fall under the federal executive branch, not the judicial branch, like most courts. And immigration cases are civil, not criminal, meaning certain due process protections don’t apply — including the right to a court-appointed lawyer.

Judge Doolittle gave each of the individuals before him a list of free and low-cost attorneys and emphasized the importance of having representation.

“[The lawyers] are often too busy to help everyone, and it can be hard to get in touch,” he told them. But the judge added that families with good attorneys win their cases more often.

The judge warned the people in the room to be careful as they looked for an attorney. They shouldn’t give money to people they don’t know, he said.

As Doolittle dealt with each case, setting new court dates for most, the room gradually emptied.

CT’s shortage of immigration attorneys

It’s not unusual for immigrants to go through court without legal representation. But a Connecticut Mirror investigation found that Connecticut stands out for having one of the lower representation rates in the country — and that matters when someone is trying to avoid deportation. As Doolittle noted in court that day in June, people are far more likely to win their cases when they have a lawyer.

A shortage of judges and immigration court staff, a recent influx of migrants to the United States and the labor-intensive nature of cases have rendered it impossible for Connecticut’s small community of immigration lawyers to meet the demand for representation.

As a result, tens of thousands of immigrants in Connecticut are left without legal support, even as stories of immigration enforcement grow more frequent, from a mother taken from her car in New Haven to men detained at a Southington car wash.

“Every time I look at [the case backlog], it just keeps growing again.” – Sheila Hayre, Quinnipiac Law Professor, supervisor at Quinnipiac Civil Justice Clinic

Even attorneys who have worked on immigration cases, like Maggie Rodriguez, formerly a lawyer with Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) in New Haven, don’t have much capacity to take on new clients with immigration cases.

“If you are taking on this case from start to finish, you’re signing up for a many-year-long representation,” she said. “Once your docket is full, it remains full for a long time.”

That’s true not only for Rodriguez but for most other immigration lawyers in Connecticut. IRIS and other aid organizations have gathered and distributed materials to help people understand their rights in immigration proceedings and when interacting with law enforcement.

“That is all that we’re really able to offer the immigrant community right now,” said Ellen Messali, an attorney with the legal aid organization New Haven Legal.

Immigrants in the U.S. illegally — those who entered without proper documentation or overstayed a visa — have the right to due process when authorities bring a case seeking to deport them.

But the immigration courts that handle these cases are overloaded, facing a backlog that has grown for nearly two decades and ballooned in 2023 and 2024. At the end of last year, the number of pending cases nationwide was over 3.6 million.

Immigration court backlog

In Connecticut, more than 42,000 cases were pending as of May, before just two judges. In fiscal year 2024 alone, more than 20,000 new cases were added to the docket. On average, cases in Connecticut take nearly 500 days to be resolved.https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/KNj5A/2/

“Every time I look at that number, it just keeps growing again,” said Sheila Hayre, a clinical professor at Quinnipiac University School of Law and supervisor at Quinnipiac’s Civil Justice Clinic.

Lawyers say the legal process can be lengthy and unpredictable in immigration court, and outcomes can vary depending on which judge is hearing a case. The judges in Hartford’s Immigration Court, for example, denied nearly 70% of asylum cases from the 2019 through 2024 fiscal years, while the national average is below 60%, according to data gathered by the research group Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse and analyzed by CT Mirror.

Since many immigrants lack access to legal representation, it often falls to judges to explain the complexities of a defendant’s various legal options.

For example, in federal court that day in June, one man told Judge Doolittle that he had hired a lawyer, but they didn’t collect evidence. Another man told the judge he wanted to keep fighting his case but had already been defrauded by an attorney. Because the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was seeking to deport him quickly, both the judge and the government attorney suggested he find a new lawyer soon so the attorney would have time to prepare to fight deportation proceedings.

“This is some good advice from the government attorney,” Doolittle said. “Don’t wait.”

Doolittle also took time to explain options to two single moms who didn’t have lawyers.

One young mother, whose daughter wore a pink dress, said she had tried three attorneys, but none would take her asylum case. The judge told her the next hearing would go forward with or without a lawyer and suggested she look into Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS). She had never heard of the program before.

But giving people extensive legal advice “is obviously not a good way for a judge to spend time,” Hayre said. In cases where a defendant’s son or daughter could be sent back to their home country, she said, judges know that an extra five minutes of explanation could end up being a matter of life or death for the child — given the threats some immigrants face back home.

“There’s nobody else to explain it,” Hayre said. “The whole thing is so frustrating.”

But even as immigration enforcement is ramping up, while case backlogs have grown across the country over the past five years, the federal government fired 20 immigration judges in February.

The number of immigration judges in Hartford recently dropped from three to two. There are concerns that immigration cases in Hartford will now take longer to process and may suffer in quality at a time when courts are already overwhelmed and expecting even more cases.

Dozens of members of Congress signed a letter to U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi expressing their concerns, including U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., and U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes, D-5th District.

The importance of legal representation

Hayre recalled the story of a Guatemalan woman she represented who was trapped in an abusive marriage. The woman, mother to two U.S. citizen teenagers, lived in constant fear.

The woman’s husband used her immigration status to threaten her safety if she looked for help.

“I have status,” her husband would tell her, Hayre said. “You have no rights in this country because you are undocumented.”

Hayre said she remembered how he would threaten his wife: “If you call the police, I will tell them lies about you, and they will listen to me because I am legal.”

“For people with very good cases where maybe their family is in danger in their home country, [the court delays are] really much more of a problem.” – Michael Boyle, immigration attorney

The woman’s husband told her if she tried to ask for custody or child support, the judge would give him custody and she would be deported.

Without access to an immigration attorney, many victims don’t realize they could qualify for protections under federal law.

The woman was able to get legal status through a program under the Violence Against Women Act. Soon after, Hayre heard from her for the first time in four months. That was the first time that she spoke in English to Hayre.

“She told me that getting status gave her a new lease on life and a new connection to this country,” Hayre said. “Divorced from her abuser, she was now working two jobs, making more money than her husband, and her kids were excelling in school. One child was starting his military service.”

Immigrants facing removal proceedings are more likely to prevail in their cases if they are represented by a lawyer. Most do not have representation.

While immigrants have the right to legal representation, they must pay for it themselves.

And lawyers are hard to find.

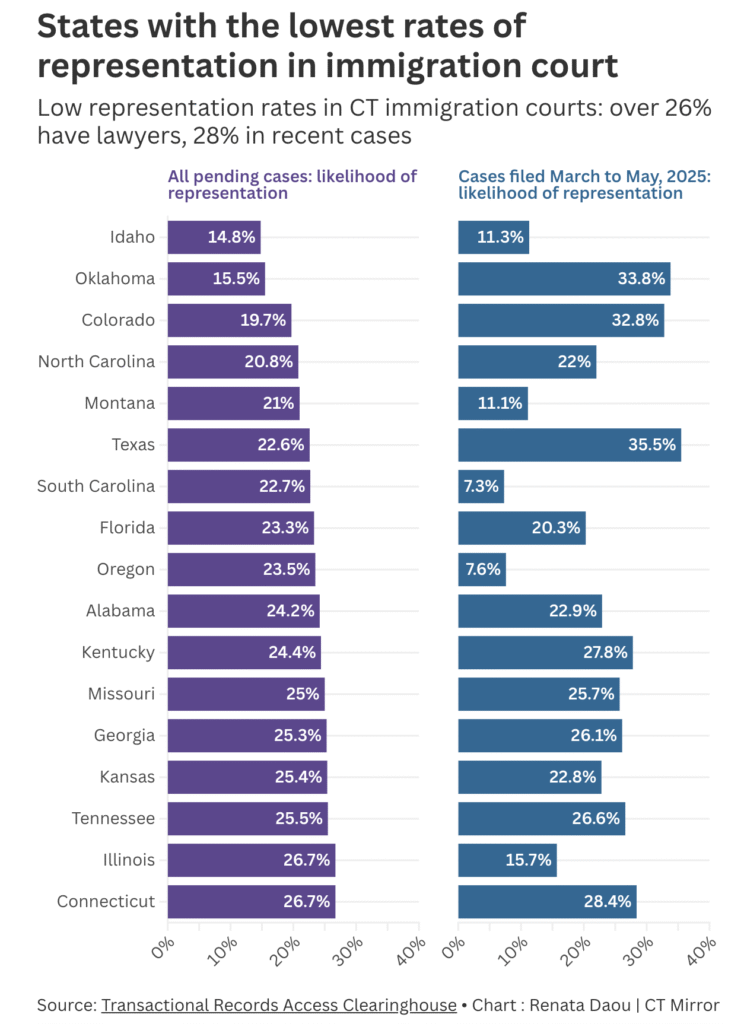

In Connecticut, just over 26% of immigrants with pending cases are represented by a lawyer, TRAC data shows. And for those with newer cases, about 28% are represented.

Compared to other states, Connecticut ranked 17th from the bottom for legal representation in immigration court cases as of May 2025.

That includes all cases that are still waiting for a decision in immigration court. Some cases may only need one hearing, while others can stretch over many years with multiple court dates, according to TRAC.

In some cases, it takes time to even be added to the court docket. Some people arrested at the border and released to pursue their cases end up stuck in limbo at the border. Their cases are not filed with an immigration court, sometimes for years.

“For people with weak cases, that’s fantastic, because they often got work authorization, nobody’s going to bother them for years. So they’re picking up extra years here,” said Michael Boyle, an immigration attorney with offices in Danbury and New Haven. “For people with very good cases where maybe their family is in danger in their home country, it’s really much more of a problem.”

At the start of the process, many people don’t have lawyers. But as cases move forward, particularly closer to a final decision like an asylum ruling, people are more likely to find legal representation. That’s why early-stage cases tend to have lower representation rates.

Cases without lawyers are often resolved faster, according to TRAC, because “without representation, more often than not, no one is available with the knowledge and skills required to effectively mount a defense.” Over time, this leaves a growing share of the backlog made up of people who do have lawyers.

For example, in the 2025 fiscal year, 74% of pending cases involved people without a lawyer, while 26% were represented. In initial hearings, 91% of cases were unrepresented, but in later-stage hearings where decisions are made, 89% of people had lawyers, according to a CT Mirror analysis of TRAC data.

It’s not clear exactly how many immigration lawyers are working in Connecticut. But if the total number of immigration lawyers in the U.S. were evenly distributed by population, it would be fair to estimate Connecticut has only about 200. And they’re expensive: Legal fees can range from $10,000 to $20,000 or more per case.

With so few available, it isn’t possible for immigration lawyers to represent every client that seeks their help.

“What if you’re a family fleeing Venezuela? How do you represent the whole family? So the lawyer is making a very hard decision of who has the strongest case,” Hayre said.

Representation and court outcomes

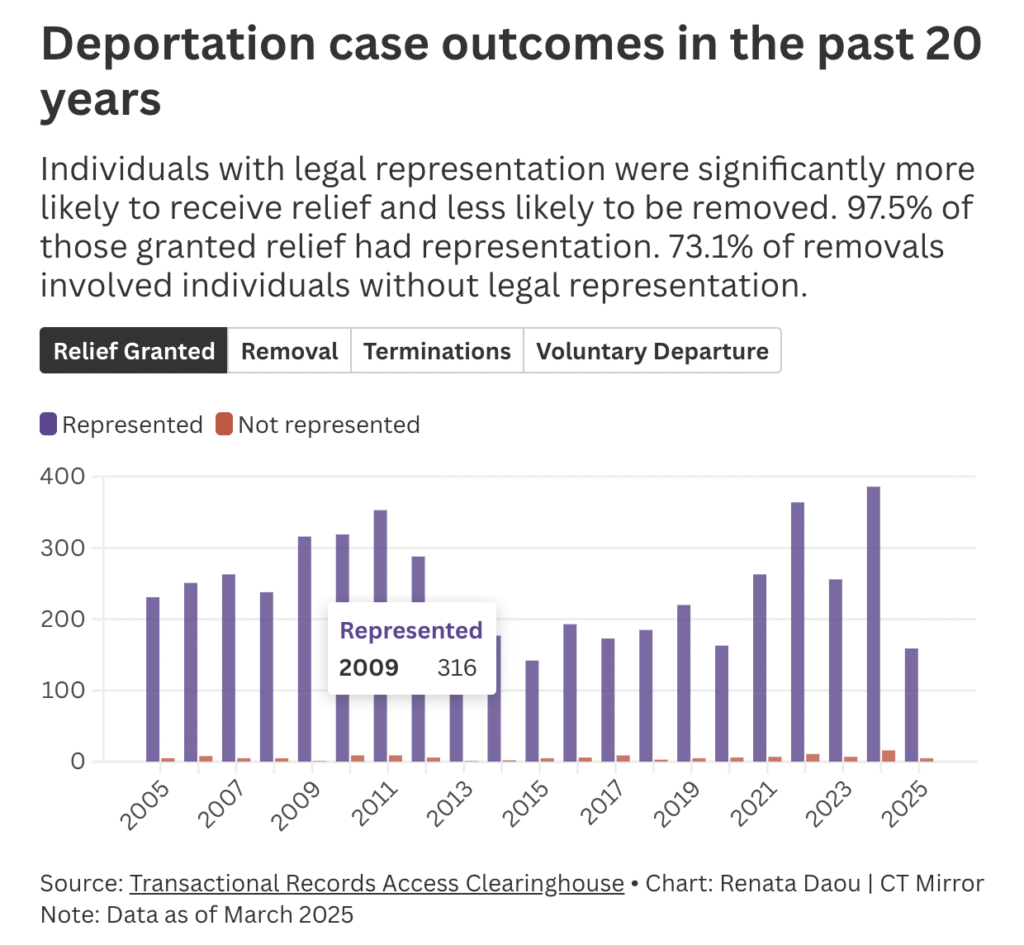

Representation plays a crucial role in deportation case outcomes. Among those granted relief, 97.5% were represented, while only 2.5% were not. Of those removed, only 26.8% were represented, while 73.1% were not.

But the growing backlog has placed mounting pressure on the entire immigration legal system, cutting down the time and resources available. So immigrants with stronger or less complicated cases often have an easier time finding representation — and a higher likelihood of winning their cases.

“People in immigration court are having their absolute entire life decided in one to two hours,” Boyle said. “It used to be, up until a couple of years ago, it used to be you at least got three or four hours.”

Getting more time if front of a judge often requires pushing back, Boyle said. Otherwise, life-altering decisions are made in an incredibly short window without adequate time to build a detailed record and establish the applicant’s credibility, he said.

In Connecticut, in asylum cases from Fiscal Year 2001 through May 2025, more than 37% of asylum decisions — involving people who are seeking relief from deportation because of conditions in their home country — were granted on their merits when defendants had legal representation. In cases where the defendant didn’t have a lawyer, roughly 10% were granted asylum or other relief, according to a CT Mirror analysis of TRAC data.

If an immigrant gets arrested and detained, representation becomes even more complicated. Some may find themselves no longer able to afford a lawyer because they’re unable to work.

“You think that you know what you might be doing for a client to help them one day, and then, within a matter of days, that option that you thought you have may no longer even be available,” New Haven Legal’s Messali said.

“Not everyone wants to work in situations where people are so traumatized.” – Ellen Messali, New Haven Legal

It also shifts the logistics of working a case, Messali said. Visiting clients in detention is an all-day commitment because there are no immigration detention centers in Connecticut.

Some of New Haven Legal’s clients are in Plymouth, Mass. Others are in Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania. Clients have also been sent to facilities even further away, leaving them far from their contacts and their families.

“We’ve had clients get sent south to Georgia,” Messali said.

Securing bonds for detained immigrants can significantly improve their chances of success in immigration court, allowing them to be home with their families and properly prepare their cases, Messali said. When released on bond, their case returns to the court’s regular docket, giving them years to find legal representation and prepare their applications. But with so few lawyers available, it still leaves many scrambling.

Those who remain detained face an expedited process, having just weeks or months to prepare for removal proceedings. There often isn’t time to find legal representation.

Remote hearings further complicate the process, with detainees appearing before a judge over a screen and relying on phone or video interpretation.

“While accessing clients who are detained out of state is very taxing and resource-intensive, we do not advocate for Connecticut to begin detaining immigrants in its correctional facilities,” Messali said. “We are opposed to immigration detention anywhere and want to see it abolished.”

Limited options

The supply of lawyers isn’t meeting demand because providing low-cost or free legal services to immigrants requires substantial funding, which “just kind of doesn’t exist” in Connecticut, Rodriguez said. That means fewer open positions for lawyers interested in representing immigrant clients in the state.

Back at the courtroom, one woman said she had spoken to three lawyers but was told that none had capacity to take on her case. Another woman had filed her petition for asylum with an attorney at a nonprofit who was later let go due to lack of funding at that organization. The woman was on two lists for legal aid services in New Haven and Bridgeport, but the clock was ticking on her case. She told Doolittle she’d looked into private defense but found it was unaffordable.

“I understand that it’s hard, and there’s a lack of funding,” Doolittle told her. The judge granted several of the individuals before him an extra year to find an immigration attorney.

People who want to practice immigration law are more likely to find jobs in Boston or New York, Rodriguez said. That leaves immigrants in Connecticut with limited options. The highest concentration of immigration cases in the state are in Bridgeport, Danbury, Hartford, Stamford and New Haven — which isn’t convenient for a lawyer licensed in Massachusetts or New York.

And the work itself is hard. Beyond the legal complexities, the emotional toll can be profound, Messali said.

“The work that my colleagues and I do is very trauma-intensive,” she said. “We work with people who have been persecuted, who have been tortured, who are terrified at the prospect of returning to their home countries. Not everyone wants to work in situations where people are so traumatized and [face] the additional challenges that come with working with individuals who have been through this kind of trauma.”

Despite the emotional toll, Hayre continues to pursue this line of work. Stories like the Guatemalan woman’s keep her going.

“I do this because of people like her — immigrants who remind me of why this country is so great, because of people who come here seeking a better life, ready to work hard in order to ensure a better future for themselves and their children.”

Brian Galliani, dean of the Quinnipiac School of Law, said Connecticut might consider funding a “right to counsel” program for immigrants, similar to a service the state provides to defendants in eviction cases.

Galliani pointed to the state of Oregon as an example, where immigrant legal representation is funded by the state through a nonprofit known as the Innovation Law Lab. That organization also partners with law school graduates who can earn a license by completing a certain number of hours of supervised legal service to clients. He said that the same model could work in Connecticut.

Quinnipiac’s Hayre said while having a lawyer is ideal, expanding legal education and courtroom support for immigrants could make a big difference — by helping them navigate the system more effectively, reducing the burden on judges and ensuring fewer families fall through the cracks.

“It may be just legal knowledge and information so that people can better advocate for themselves and put their stories together on their own,” she said.

With the immigration court system under so much stress, and with immigration enforcement policy changing rapidly, many immigrants have a difficult choice: remain in the U.S. and face rising uncertainty, or return to a home country and face potentially life-threatening circumstances.

Messali said she hopes Connecticut residents, many of whom are her clients’ neighbors and coworkers, can resist what she sees as misrepresentations of immigrants. Instead, she hopes they’ll try to understand the pressure many immigrants are under — and their resilience in the face of it.

“The biggest thing I wish people knew is just how wonderful my clients are, just how wonderful the immigrant communities in our state and throughout our country are — how hopeful, decent, hard working, giving and generous they are,” she said.

A lack of immigration lawyers in CT means big court backlogs was originally published by CT Mirror and is republished with permission.

Renata Daou is the data reporter for CT Mirror.