CT Latino News’ series—Hartford Children’s Health: Equitable Access—explores responses to complex systemic and cultural barriers across Connecticut’s capital that impact the daily health of its youngest residents. About 28,000 children and youth live in Hartford, one of the state’s most diverse communities that continues to address a variety of longstanding health-related disparities.

HARTFORD—Weekday mornings are a flurry of packing backpacks and deciding on outfits for the day for most children. Across Connecticut—where about 327,000 guardians work hourly—parents also prepare for their own busy day and students caught up in the morning rush can get into the habit of skipping breakfast or grabbing something quickly to go.

“Sometimes they say, ‘well, I have breakfast at home,’ and you would try to find out what that is…breakfast will be like soda or Pop-Tarts or unhealthy choices—quick snacks or things that are easily accessible, which is sometimes not the best,” said retired middle school nurse Veronica Laing who worked in the Greater Hartford community for ten years.

Every day, about 28,000 Hartford children and youth make their way to and from school, the majority walking an average of 0.25 miles to their school bus stop or being driven to school by a guardian, according to Hartford Public Schools Superintendent Dr. Leslie Torres-Rodriguez. Laing recalls these busy school days when her two children walked to and from St. Joseph Cathedral School in Hartford.

“Some parents feel it’s safer to drive their kids to school…because of predators and safety concerns,” she explained in a phone call. “But you find that kids do not get the exercise they really should be getting from doing those kinds of brisk walks.”

An inconsistency of balanced meals and safe, enjoyable opportunities for regular exercise will weaken health, just like poor sleep quality and mental health can. These four areas of well-being, along with genetics, play significant roles in a person’s likelihood to develop obesity, which is prevalent in about 38% of adults across Hartford.

Our bodies respond and adapt to our daily habits, resulting in immediate as well as longer-term effects. So, we hear about the importance and pressure of having “healthy lifestyles.” Still, these discussions tend to ignore certain complexities and imply that we all have the same access to resources and that having certain lifestyles is always a choice.

“Hartford doesn’t really have a grocery store in the entire city,” said Dr. Melissa Santos, Division Head of Pediatric Psychology and Clinical Director of the Pediatric Obesity Center at Connecticut Children’s. “If you don’t have transportation, how are you purchasing fresh fruits, fresh vegetables… how are you getting it back home in a safe way? Where do your kids play? Do you have a built environment that allows for parks and green space? Or are you in a multi-family house where your kid can’t run or jump because you’re going to disturb the neighbors? We also know that obesity tends to be genetic. So, chances are other people in the family have obesity as well. So, then how do you help the whole family start to make changes?”

Hartford’s Rising Obesity Rates

In 2023, Hartford had one of the highest prevalences of obesity across Connecticut, which has an average obesity rate of 29%, according to DataHaven’s latest Hartford Equity Report. About 42% of the capital’s Latino population and 39% of its Black population have been diagnosed with obesity, compared to 28% of the white population.

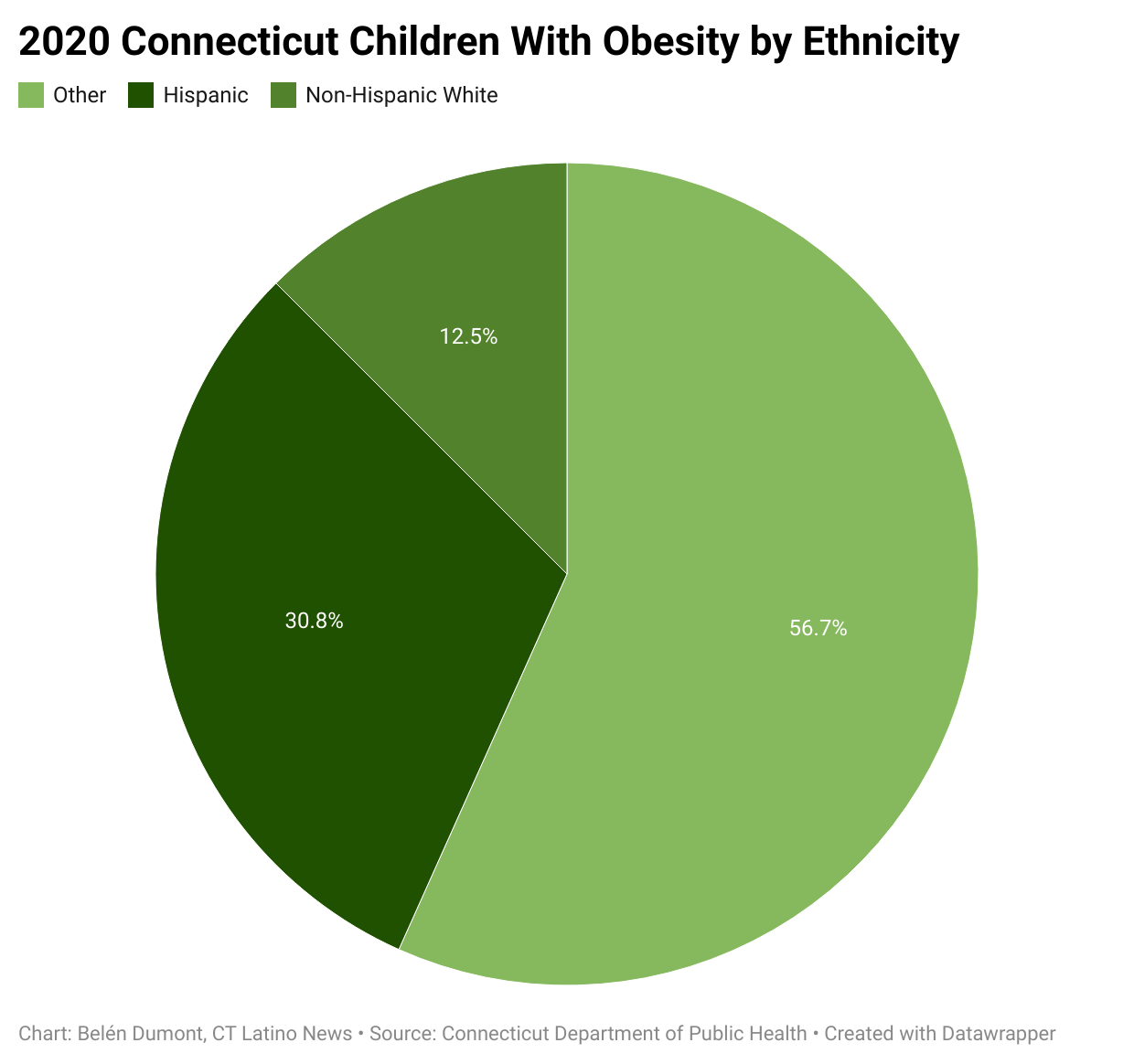

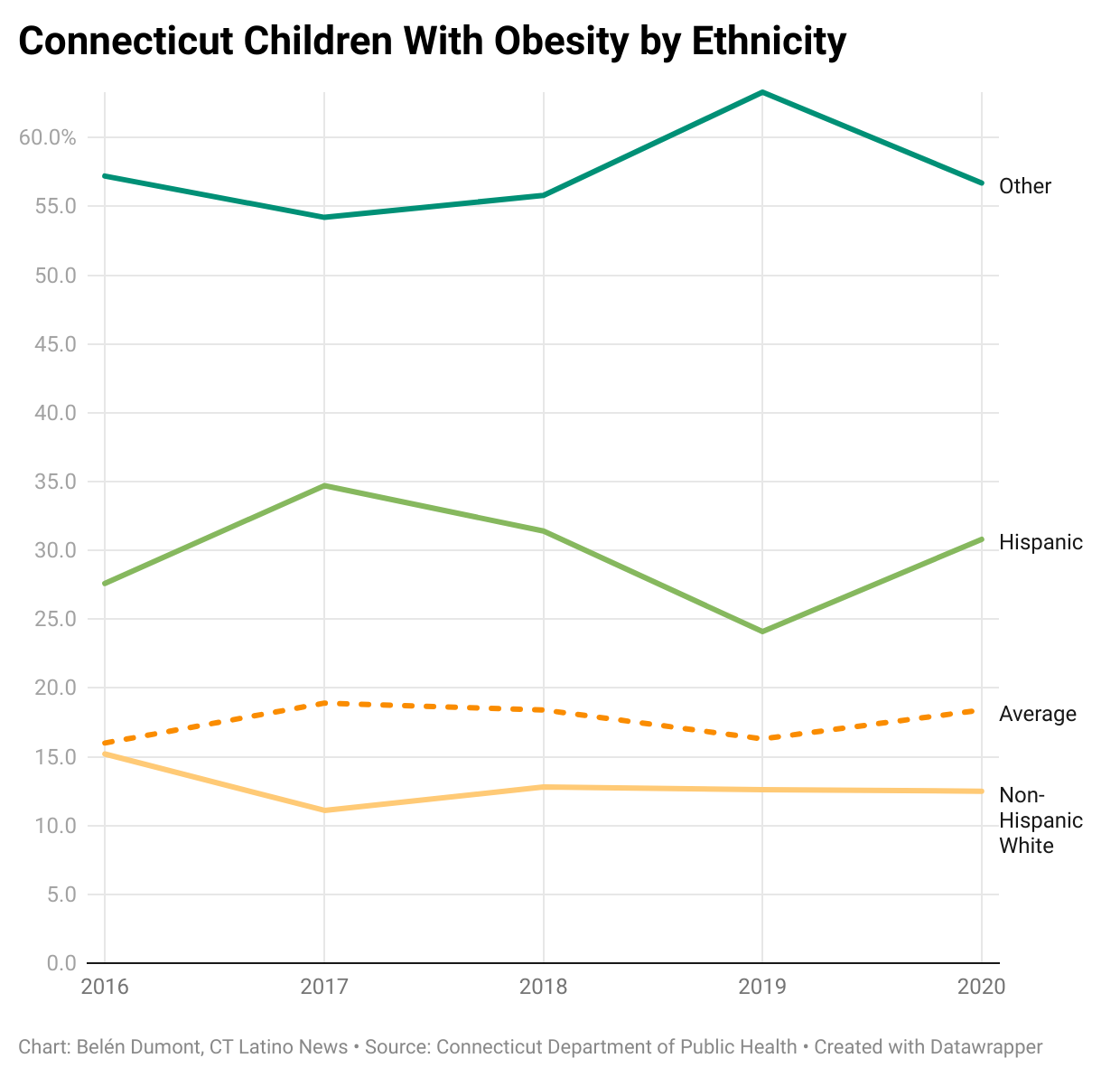

Childhood obesity rates in Connecticut show similar racial and ethnic disparities. The Connecticut Department of Public Health reported that about one in five children from 5 to 17 years old across the state were diagnosed with obesity in 2020. About 30.8% of Connecticut children experiencing obesity identified as Hispanic, while 12.5% of children across the state with obesity were Non-Hispanic white, according to the study. There was no data available on non-Hispanic Black children.

Statewide studies have continuously aligned with national trends over the years, reporting that Black and Hispanic children are significantly more likely to be overweight or obese compared with white children.

Across the state, childhood obesity has fluctuated in recent years: Among children 5 to 17 years old, approximately 13.4% had obesity in 2015, 16% had obesity in 2016, 18.9% in 2017, 18.4% in 2018, and 16.3% in 2019, according to the 2019 Connecticut Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS).

Rising obesity rates among children and adults remain a top medical concern as this chronic disease is a common high-risk factor for heart disease, diabetes, certain cancers, and strokes—the country’s leading causes of death.

New Emphasis On Early, Intensive Treatment For Children With Obesity

In January 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released its first in-depth guideline on childhood obesity diagnosis and treatment in 15 years. The AAP emphasizes the complexity and severity of obesity, explores the role that social determinants of health play, and advises pediatricians to offer treatment options early on at the highest available intensity to children with obesity. Previous AAP guidelines recommended delaying treatment and “watchful waiting” to see if children would outgrow obesity.

“[The guidelines] shift the conversation to remember that obesity is a medical condition. It is not a lack of willpower. It is not anyone’s fault,” Santos said. “It really is a disease that comes from many factors that we don’t truly fully understand and that we have to be able to offer families, when appropriate, all the treatments that are the right thing for them.”

The AAP report instructs providers to focus on obesity-prevention efforts among children and youth, as reducing excessive weight gain is more difficult once it’s established in adulthood. The report outlines evidence-based recommendations such as motivational interviewing, intensive health behavior and lifestyle treatment, pharmacotherapy, and metabolic and bariatric surgery—all offered at Connecticut Children’s Obesity Center based in Hartford. The AAP states that each approach must be tailored to the individual, considering the child’s health status, community context, family system, and available resources.

The updated guidelines represent progress that health advocates have long-called for in addressing obesity as a serious, chronic, highly prevalent disease that requires medically-assisted treatment and comprehensive preventive resources. Obesity continues to carry the stigma that diminishes the disease’s complexity and underemphasizes societal structures and barriers that contribute to such widespread health conditions.

“I appreciated that kind of conversation of really recentering this on the disease state of obesity and recentering it that obesity is also a product of many things that exist in our society…that impact people differently and that we can’t hold them accountable for that,” Santos said about the guidelines.

Although obesity rates have rapidly increased over the past several decades, contributing to high prevalences of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancers, and strokes—some of the leading causes of death in the U.S.—there’s a long-history of controversy surrounding obesity’s classification.

Obesity was first declared a disease by the National Institutes of Health in 1998, then the American Obesity Society in 2008, and the American Medical Association in 2013—with the support of numerous medical societies.

Recognized as the nation’s most influential medical association, the AMA’s decision to classify obesity as a serious disease sparked research efforts on evidence-based prevention and treatment, increased relevant resources and services, and national debates, including how health care policies and insurance coverage would acknowledge the historically stigmatized disease.

Culturally-Informed Nutrition Education

Hispanic Health Council Chief Program Officer Sofia Segura-Perez has studied and reported on how breastfeeding interventions have impacted on women of color across the United States. She brings her expertise to the organization, where their team educates local Hispanic and Latino communities on best health practices and connects them with various free resources.

“Breastfeeding has been associated with lower levels of childhood obesity later in life,” Segura-Perez explained in a Zoom call. “Breastfeeding without a schedule is the best way. It’s the best childhood obesity prevention during the first six months of the baby’s life.”

In August, Segura-Perez and her colleagues hosted an educational event for World Breastfeeding Week, where they shared findings from her research and openly discussed concerns and challenges new mothers were experiencing regarding their infant’s nutrition.

“To understand these factors of obesity, you need to have a cultural approach. Mainly for us, as Latinos, there is a preconception that if you eat a lot you are more healthy or if the mom eats a lot during pregnancy the baby will be more healthy,” shared Hispanic Health Council Marketing Manager Alicia Diaz. “We need to teach our community that those are old school things and that it does not depend on the amount of food that you eat, it depends on how healthy or not those foods are.”

The Hispanic Health Council is a community-based organization in Hartford that has served surrounding communities of color for the past 40 years through in-depth research, advocacy, and culturally-resonant services.

“It is important to understand the culture and to be respectful…I think that’s why they’re very important, the community-based programs. We need to understand their culture but also we are a part of that culture,” Diaz said.The majority of the Council’s staff identifies as Latino and are from the community or similar communities, she explained.

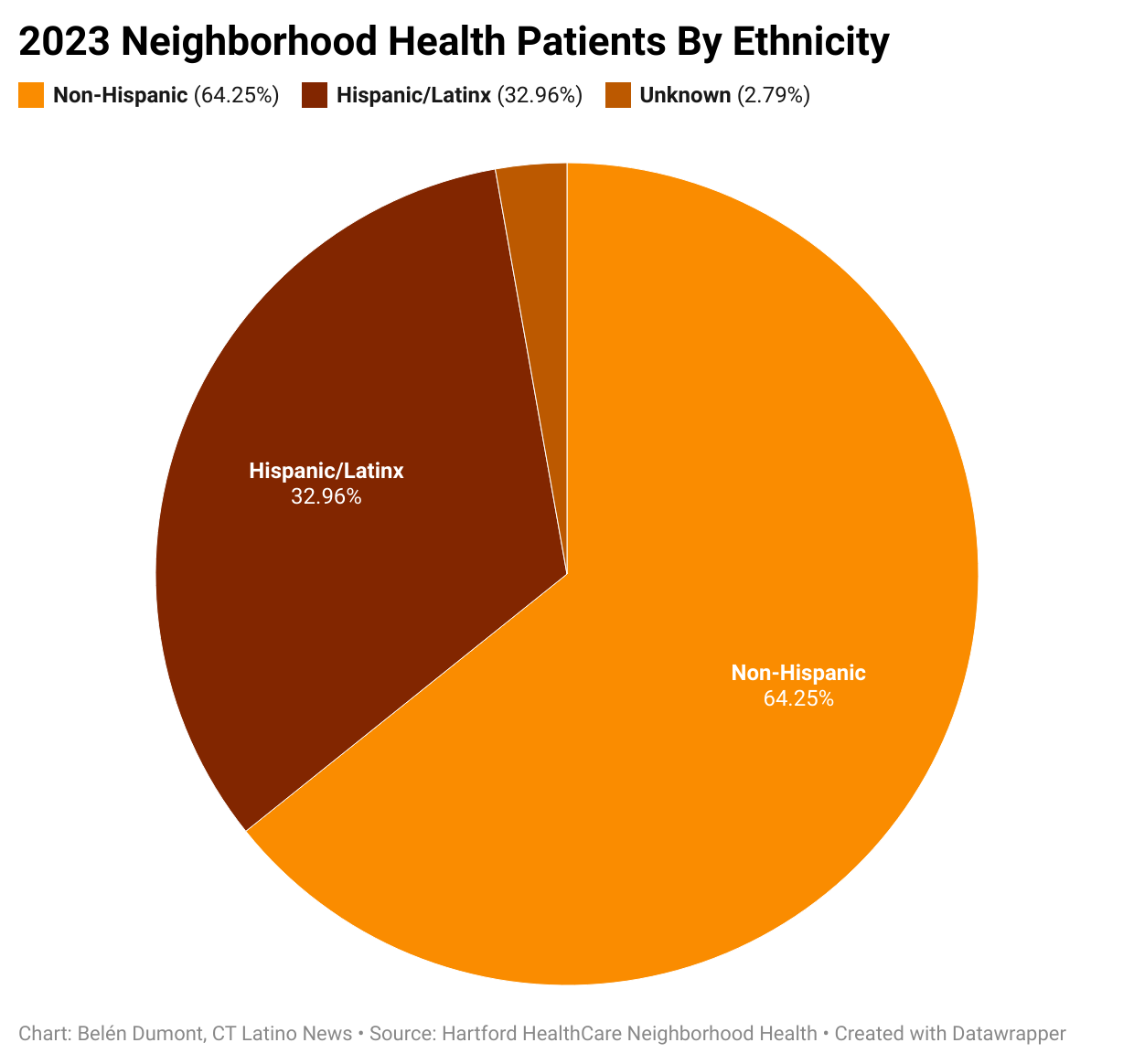

The Council opened its new Family Wellness Center in Frog Hollow—a predominantly Black and Hispanic community—this past August with the support and collaboration of community partners, including Hartford HealthCare’s Neighborhood Health Clinic, to offer a wide range of free, bilingual services. The clinic sees about five to 25 patients daily and has served a total of 2,234 patients in the past year, according to System Manager of Neighborhood Health Operations Dawn Filippa.

Neighborhood Health Clinic Care Manager Nidia Rivas shared that the clinic has seen a high prevalence of diabetes within the local community. Although their staff looks to educate residents on eating well and exercising regularly, it’s difficult for individuals trying to meet their most basic needs.

“Sometimes it’s hard for the patients we serve because they hardly have anything to eat…When you’re in that situation you eat what you have, you eat what you can get,” Ririvas said. “If you don’t have your basics covered, how can you move further? Because that puts more pressure on them and they’re going to feel worse.”

ConnectiCare Nurse Karin Remicio has worked in the Hartford County community for nine years and has also seen a high prevalence of diabetes along with heart disease, strokes, and high blood pressure among patients. She emphasized factors like the high-cost of healthy foods, insufficient nutritional education, and culture that can heavily influence people’s health.

“Different cultures, Hispanic cultures too, might be a little more resistant to that [lifestyle] change because of those barriers, because of the parents working, because financially they can’t afford certain foods…” Remicio said of families’ struggle to be as physically active and nutritious as they would like.

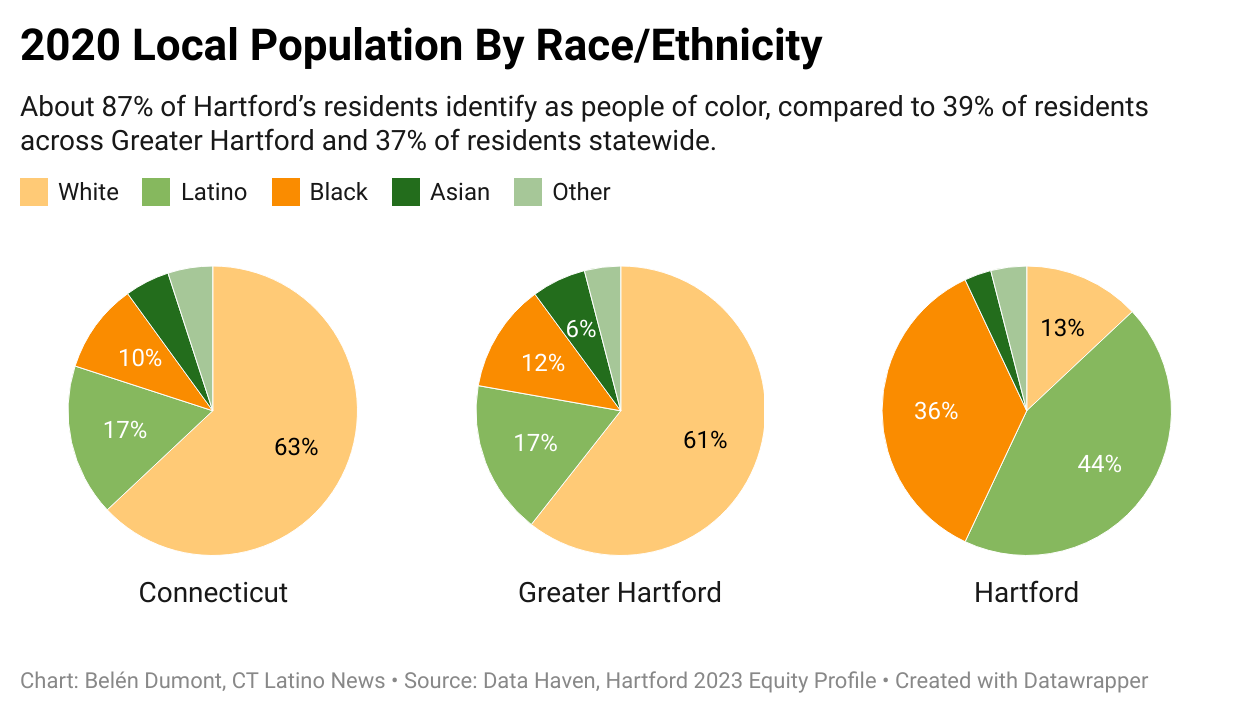

Community members and healthcare providers have emphasized the role of culturally informed education in residents’ health. Hartford is home to one of the state’s largest communities of color, with Latinos making up 44% and Black residents representing 36% of the capital’s population.

“When I was growing up…it was more quantity. It was more just having food…our parents just wanted to make sure that we ate,” explained Remicio, who is originally from Lima, Peru. “But with my kids and this new generation, I think we’ve become more educated either through their schools, or our own careers, or our own experiences outside our family and within our family. So, now that we are raising our kids, it’s more quality instead of quantity.”

In Hartford, 35% of Latino residents, 31% of Black residents, and 17% of white residents experienced food insecurity, with the average rate of food insecurity across Greater Hartford at 13% and across Connecticut at 14%, according to 2021 data provided by DataHaven.

“When you have higher rates of food insecurity or you’re a parent who grew up in poverty or…with food insecurity, it’s really hard not to purchase in bulk. Because you’re gonna want to know that your pantries are full of food. You’re going to want to know that your child is never hungry,” Santos said. “Oftentimes, when kids will be like, ‘Mom, I’m hungry’, even when you know [they’re] not hungry, that breaks a parent’s heart. Particularly if you knew what it was like to go to bed hungry. You’re never going to let your child have that feeling you had.”

Healthcare experts working within communities of color are looking at the balance between educating parents and children about the importance of healthy eating while respecting and acknowledging the role that access and culture play.

“I think that’s kind of part of the reason why obesity, especially in the Hispanic culture, is so big, because we use food as comfort…instead of saying, okay yes, it’s comfort but let’s really think about it and of how good it is for us, our kids,” said Remicio. “Food brings us together, brings happiness, [treats] sadness, stress, anxiety. It’s like, ‘oh, you’re anxious here, have some food’ or ‘you’re sad, here, have some.’”

“When we talk about our racial and ethnic minorities, I think there are some unique things that make obesity treatment different. Oftentimes the guidelines for obesity treatment don’t take into account their cultural norms, their traditions, the things that really allow them to celebrate their culture,” shared Santos. “Oftentimes, I’ve seen recommendations where the first thing is to reduce rice and, for some people, that’s a key component of their meals. And that’s not the reason why anybody has the weight problem that they have.”

Motivational Interviewing to Identify Additional Health Barriers

As community and medical institutions raise awareness of the importance of culturally-responsive health services and resources, new healthcare practices that can better support diverse populations continue to emerge.

Santos has co-authored reports evaluating the impact of structural racism on racially disproportionate childhood obesity rates and the benefits of motivational interviewing among such communities. She pointed out that the Obesity Center assigns patients both a pediatrician and a psychologist to assist families with forming a treatment plan.

“What really motivational interviewing does is allows us to partner with our patients and really changes the dynamic because I think sometimes in healthcare, it’s sort of like because you get to call yourself ‘Doctor’ you’re the expert, [that] you come in knowing all the things, but I don’t. I go into that room knowing I’m the least informed person in that room,” Santos said. “It’s only when I partner with families when I understand what some of their difficulties are.”

Motivational interviewing involves open, in-depth conversations between providers and their patients where the provider pays special attention to the priorities and concerns of the individual along with the specific circumstances and environments in which the patient lives.

“Any parent is going to want to do the right thing for their child’s health,” Santos said. “If a parent can’t do that…it’s because something is getting in the way. Sometimes it may take a little bit of digging and building that trust and relationship. I think, obviously, the other part of this whole thing is that the health care system has never been kind to racial and ethnic minorities. So, there is that barrier and there is that relationship that has to be formed.”

Santos added that motivational Interviewing is a non-judgmental approach that looks to reduce the shame associated with stigmatizing conditions and circumstances.For providers, the practice may draw further awareness to issues like transportation costs, limited time off work, and other barriers that disproportionately impact underserved populations and may interfere with patients’ access to treatment.

While Connecticut covers health insurance for all children under 18 years old, Santos explained that “it’s free if you can get there.”

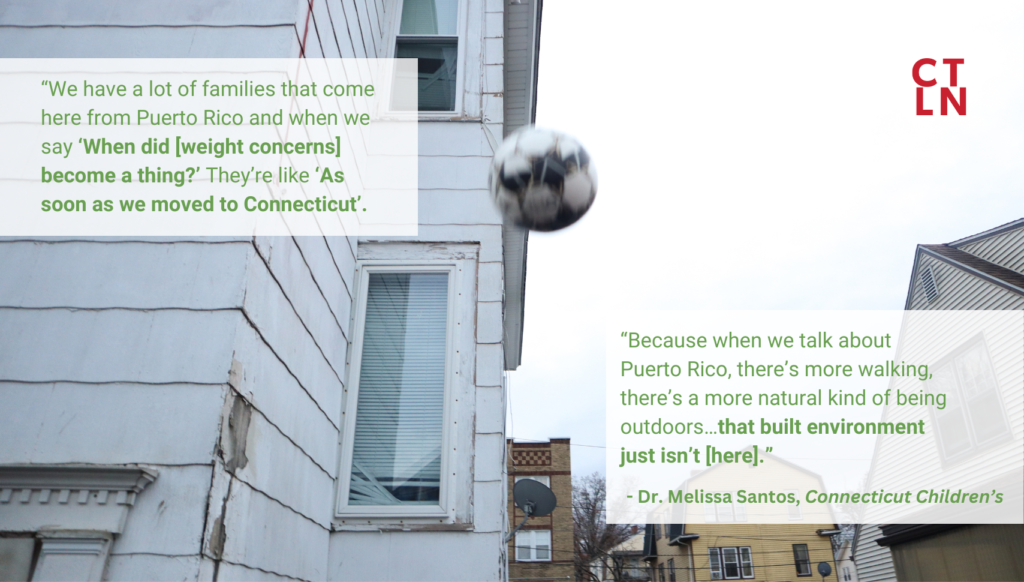

Hartford’s built environment is a shared concern among community members and local healthcare providers. In such urban areas with extensive communities of color, there’s a lack of easy access to grocery stores with fresh produce and healthy beverages and insufficient safe green spaces for families to play and walk across.

“We have a lot of families that come here from Puerto Rico and when we say ‘When did [weight concerns] become a thing?’ They’re like ‘as soon as we moved to Connecticut’,” Santos explained. “Because when we talk about Puerto Rico, there’s more walking, there’s a more natural kind of being outdoors…that built environment just isn’t [here].”

Santos pointed out that aside from diet and exercise, mental health is another, much less recognized and discussed, aspect of obesity. Research shows that obesity often comes with comorbid mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and suicide. This comorbidity is more present among youth of color—particularly Black children and adolescents—who may experience higher levels of psychological stress from racially motivated discrimination.

“We also have to take into account the whole child and understand that physical, emotional, and environment [factors] are all going to play together,” Santos explained. “I think the more that we focus on the social determinants of health of the built environment, access to care, and really change the conversation of obesity as a disease that needs to be respected and treated just like every other medical condition that goes a long way to help families.”

The next piece in this series, Hartford Children’s Health: Equitable Access, highlights community efforts that offer children and youth in the Hartford community accessible fitness opportunities. Support CT Latino News’ reporting by completing and sharing our brief survey, “Children of Hartford & Exercise”, below. Para acceder la encuesta en Español haga clic aquí.

Upcoming stories will also dive into community resources that address food insecurity and examine nutrition and environmental education within Hartford.

Belén Dumont reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 National Fellowship.